ABOUT US

The Oliver Experience

The Oliver Inn is a destination Airbnb-style boutique hotel in the historic downtown Duluth Arts and Theatre District. Built in 1889, the hotel was once the original City Hall of Duluth which went through several iterations of use before becoming The Oliver Inn in early 2022.

This storied space excites history lovers, preservationists, fitness enthusiasts, naturalists and curious travelers. Its interior is an eclectic mix of old and new and was renovated with sensitivity to Oliver Traphagen’s original blueprints. Creating a hotel space with minimal disruption to the original blueprints was a challenging, yet, incredibly rewarding experience for us. The outcome, we hope, is like visiting the home of a well-traveled friend. Little quirks and surprises await you at every corner. And while there is an abundance of places to explore in the neighborhood, you could spend an entire afternoon just soaking in the on-site amenities: our fitness center, a spacious Scandinavian sauna, and an underground speakeasy (The Rathskeller).

We are thrilled for the memories you are about to create here at The Oliver Inn.

The HISTORY

The historic Oliver Inn, located directly above The Rathskeller, is set in Duluth’s original 1889 City Hall overlooking Lake Superior, and blends timeless luxury with modern comforts for a unique Duluth experience.

Our building was designed as Duluth’s original City Hall in 1889 by renowned architect Oliver Green Traphagen who left an undeniable imprint on the City of Duluth. In addition to Old City Hall, Mr. Traphagen’s design portfolio included the infamous Oliver G. Traphagen House, Munger Terrace and dozens of inspired buildings throughout the city.

When we created The Oliver Inn, special care was taken to preserve the historic elements of this significant building, retaining much of its original character while animating the space with new artistic perspectives that give voice to contemporary ideas about what it means to be a vibrant growing city in the new “roaring 2020s”.

Each of the 13 rooms at The Oliver Inn tells a story about a unique Duluth personality whose courage to live their dream shaped the city we all know and love today.

Conceived as an economical place for students and adventurous travelers to stay and formed on the European traveler hostel model, Swedetown was developed for The Oliver Inn.

Hardworking and strong, over 1.2 million Swedes found their way to America — starting in 1860 and continuing through the 1930s.

Businessmen from Duluth and the Iron Range recruited Swedish immigrants to come to northern Minnesota, where they worked on building railroads, logging the woods and mining the earth.

In a thirst for adventure and making his fortune, young Emil was among Swedes who, in 1910, made his way across his own country conveyed by a rowboat, long walks and trains, crossed the Atlantic Ocean, was processed in New York and took a train to Two Harbors to join his brother.

He and other immigrants toiled at the docks, unloading iron ore from the mines of the Vermillion Range. It was dangerous work as the oar stuck to the railcars and had to be steamed loose. Emil’s job entailed getting the ore into ships, which crossed the Great Lakes to feed steel mills in the East. In the winter, workers were laid off but later, Emil got better work in factories associated with the Duluth and Iron Range Railroad, a mighty concern that created much of the need for workers on Duluth and the Iron Range.

The Swedish population of Minnesota grew to 12 percent and they brought with them their culture, such as the Lutheran Church. Swedes were drawn to Minnesota for the farmland and the landscape so much like their homeland.

In June of 1869, 200 Swedish immigrants, who came to build railroads, received a grand welcome into Duluth.

As Dr. Thomas Foster described in The Minnesotan: “The spectators on the dock cheered the boat…and cheered as well the sturdy and respectable looking immigrants just reaching their abiding place…. Not only did the people on the dock cheer, but all along Minnesota Point, as the boat steamed within near view, the ladies waved their handkerchiefs and the men hurrahed, while even at more distant points… the hurrahs were caught up by the people until the doomed woods re-echoed with the shouts.” Foster also pointed out that the group of new arrivals included 13 families “with a goodly proportion of stout, healthy, and intelligent looking girls.” Unfortunately, construction had hardly begun on a house for “for the accommodation of Emigrants.” The immigrants had to find housing in shanties along the shore from Rice’s Point to Fond du Lac. Eventually Northern Pacific built two Immigrant House at 5th and 6th Avenues North along the tracks of the Lake Superior & Mississippi Railroad.”

Swedes formed the backbone of Minnesota, first by their backbreaking labor and then through the establishment of churches, colleges and their success in politics. Europe’s loss became America’s gain as many modern Minnesotans can trace their bloodlines to the adventurous and hardworking Swedish immigrants.

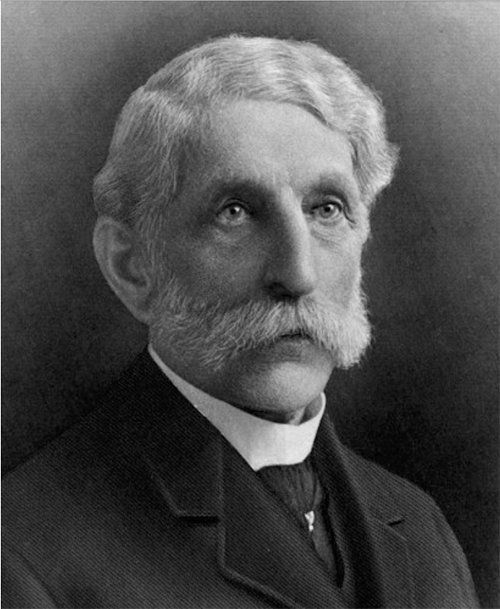

GG (Guilford Graham) Hartley was a contemporary of James J. Hill and Chester Congdon. He was instrumental in developing almost every industry in Duluth and Northeastern Minnesota — even branching into North Dakota.

He married Carrie Woodward in 1883 in Minneapolis and she remained a Duluth resident from 1885 until she died. Before that, at age 18, he went to Brainerd and worked in logging. He used cattle to break land in North Dakota and branched off into general merchandise, hardware and contracting. He also served in the Minnesota Legislature. In Duluth, the couple raised five children, including daughter Jessie who married into the Congdon family.

Hartley’s steady hand was turned to railroads and building the bridge between Duluth and Superior.

His Allendale Farm in Woodland was one of the first to produce celery in the nation. The farm later became the Hartley Nature Center. GG also owned Island Farm up north where he raised Gurseys and farmland in Dakota where he raised Aberdeen-Angus hybrid cattle.

The Hartleys built a spectacular home at 1305 East Superior Street, which was demolished in 1954. The home boasted of electricity, a telephone and spectacular architectural amenities. Across the street, there was a home for the stable man and a cabin that GG escaped to. Carrie told friends that GG once “ripped the telephone right off the wall because it rang all the time.”

He also collaborated on the building of the Hartley office building on the big lake, which was four stories on one side and two on the other. He had a hand in the development of St Paul’s Presbyterian Church and the Kitchi Gami Club.

GG was involved in logging, mining, wholesale goods, dry goods, shoe manufacturing and more. He platted towns on the Iron Range and in North Dakota. Socially, he helped establish the Northland Country Club and the Orpheum Theater, a popular vaudeville venue. He also owned the Duluth News Tribune newspaper.

Wherever there was a buck to be made, a town to found or a business to run, GG Hartley was there. When he died, at age 68 in 1922, his fortune was worth $40 million in today’s dollars. He had attended a concert at the Presbyterian Church the night before but had been weak for three years after suffering a bout of influenza.

The Duluth New Tribune, which he sold in 1921, honored him with these words: “His love of life was intense, his happiness when surrounded by the members of his family were illimitable, his interest in all the affairs going on about him was of the keenest. His mind was ever conceiving new projects. Planning and accomplishing was his life.”

Mary McFadden was a writer, poet, journalist, lobbyist and fierce advocate for women getting the right to vote.

Born to Irish immigrants in Canada, her family moved to Graceville, Minnesota, where she grew up. Her mother died giving birth to her 13th child.

McFadden attended the University of Minnesota and by age 24 had gigs with both the Minneapolis Times and working at the state capitol as a stenographer.

In 1903, at age 28, she became a full-time reporter for the Duluth News Tribune. Her excellent articles lead to her having a weekly, then a daily, column. Her commentary contained news of the day, witty asides and poetry — her own writ and others.

Eventually, she was named editor of the News Tribune and began to campaign for women’ rights.

“As soon as a woman demonstrates that she can sharpen a pencil correctly, she begins to be feared by men,” she wrote. And: “Actions of ‘suffragettes’ have been criticized as unwomanly. Just how a woman can do anything unwomanly isn’t quite clear to the analytic members of the sex.”

She was a great booster of Duluth, in favor of preserving nature and against a tonnage tax that she believed would hurt the iron ore industry.

In later years she left Duluth, started her own magazine, worked as a war correspondent and settled in New York City. But she never forgot the beautiful Northland, as depicted in her poem, “Canoe Song.”

“Canoe Song,” By Mary McFadden

The low song of winds in the pines is atune

To the witching night hour and you;

The lake is asheen in the light of the moon,

And here is a waiting canoe.

Out in the light

Of a summer night,

On the shining inland sea;

Away with you

In my light canoe—

Who would not envy me?

A bonfire flares at Oatka, and gleam

The light points at Allouez bay;

The soul of the night is as bright as a dream,

And the little canoe drifts away.

The low winds croon

Beneath the moon,

And the shadowy pines reply.

Under its beams

On a sea of dreams

We are drifting—you and I.

(from “Sabbath Diversions,” Duluth New Tribune 5.19.1907)

As you roam the halls of The Oliver Inn, know that the man it is named for designed dozens of buildings in Duluth and elsewhere.

Born in New York in 1854, Oliver Traphagen moved to St. Paul in the 1870s, working as a carpenter for George Wirth, a prominent architect there. Wirth's commissions in Duluth brought Traphagen here to oversee Wirth’s projects, having become a draftsman and Wirth’s partner.

Wirth returned to his native Germany and Traphagen threw his lot in with Francis Fitzpatrick, and, together over the next six years, the two designed Duluth’s premiere buildings of the day.

The first incarnation of this Oliver Inn was as the Duluth City Hall, circa 1888, and next door, in 1889, the city jail was built.

Many high-toned east end homes were designed by this partnership and other Duluth buildings include Phoenix Block, 1890, burned 1995; Fitger Brewery Boiler House, 1890; A W. Wieland Store, 1890; Hoppmann Building, 1890 razed 1966; Lester Park Hotel, 1890, razed 1902; Costello Block, 1891, razed 2007; Lyceum Theater, 1891, razed 2007; First Presbyterian Church, 1891; Incline Pavilion, 1891, burned 1901; Duluth Drygoods, 1891, burned 1899; Selleck Block, 1891, razed 1905; and many, many more.

He designed buildings and high-end homes on his own, with Wirth, with Fitzpatrick and in other cities as well. The years he was in Zenith City, 1886 to 1896, were extremely prolific and instrumental to Duluth’s growth and expansion.

Both Traphagen and Fitzpatrick left Duluth in 1896.Traphagen moved to Hawaii where he was responsible for at least 35 buildings constructed in Honolulu and Hilo between 1898 and 1907. His doctor advised a warmer climate for Traphagen’s ill daughter. He moved to San Francisco after the 1906 earthquake and fire,but designed only one building there before retiring. He died in Alameda, California in 1932.

As you admire the wonderful details and spectacular woodwork of this grand and magnificent historic architectural treasure, it’s comforting to know that Oliver Traphagen is remembered and honored for his contributions to American architecture.

“One day, this region will be covered with iron mines worth “more than all the gold in California.” – Lewis Merritt

Unearthing buried Minnesota treasure would end bitterly for the Merritt family, whose discovery of iron ore on the Mesabi Range changed Duluth — and the world economy — forever…

In 1890, an expedition led by Alfred Merritt discovered large deposits of soft hematite made of 65 percent iron. Decades earlier — in 1866 — their father, Lewis, traveled to Lake Vermillion in search of gold but returned empty-handed.

The Merritt family began their search at the prompting of Lewis. Lewis was smitten by a chunk of iron ore he was shown during his Vermillion adventure that led him to believe that the mineral could be lurking under the surface in Northern Minnesota.

The Merritts named the new iron range Mesabi, Ojibwe for “Giant Mountain” and their first mine became known as Mountain Iron.

To move the ore, the Merritts built the Duluth, Missabe and Northern Railway and the ore docks of West Duluth. The first shipment of iron ore was sent to Allouez Bay in Superior in October 1892 and wasn’t delivered to the new Duluth docks until 1893. Although Lewis Sr. and his wife Hepzibah raised eight sons, it was Leonidas, Alfred, Cassius and two nephews, Wilbur and John, who were hands-on in the mining operation. Brother Lewis Jr. and his son Hulett were investors.

To finance their growing operation, the Merritt family was forced to borrow money from John D. Rockefeller. Leonidas Merritt cut a deal with Rockefeller — consolidating their mining interests into the Lake Superior Consolidated Mines Company. Rockefeller then poured $2 million more into the Merritt Mines.

The Merritts’ fortunes sank with the economy. The Depression of 1893 worsened and the Merritts were no longer able to stay afloat. In January of 1894, the Merritts were forced to sell their stock in the consolidated company to Rockefeller, leaving them with nothing but dusty pockets and hollow memories of what once was.

Cassius Merritt died in 1894 — a death that Leonidas blamed on Rockefeller, Lewis and Hulett — who later profited from Rockefeller’s hostile takeover. Nephew Hulett — the now black sheep — fled to California and would eventually become known as the richest man in California.

Hailing from a creative family, Roger Munger began his career with a music store in St. Paul and performing in an orchestra. His brother Gilbert was a renowned landscape painter.

Munger married wife Olive Gray in 1858 and they later descended on Duluth, ready to invest in everything and anything. Arriving in Duluth with the other Sixty-niners, Munger was a big part of the early development of the Zenith City.

Through his entrepreneurship, Munger bought a sawmill and built another, got a coal dock going and a grain elevator. Serving on the school board and the city council, he continued his whirlwind pace — development of an opera house, flour mill and board of trade. He was part of cutting a shipping canal across Minnesota Point and also involved with the Spaulding Hotel. (We hope he would be amused to know that his name adorns a restored hotel room in an equally historic Duluth building).

The Munger’s mansion hugged the hillside with great views. The Mungers were among the few early Duluthians with enough money to build themselves a grand home, and, with free lumber from their own mills, the elaborate and ornate two-story Italianate design featured a low-pitched roof with an overhanging eave and topped with a cupola. Tall, narrow Roman-arch windows looked out from the second floor. Accessory buildings included an elaborate carriage house to the east and a lovely gazebo on the lawn along East Piedmont Avenue, which was renamed Mesaba Avenue in the 1890s. Looking out their windows, the Mungers could savor a view of the bay and the vibrant, expanding community below them.

Later, Munger developed Munger Terrace, the chic address at the time, with three-story townhouse units each full of luxury amenities such as grand staircases and skylights. Brownstone material for the exterior was mined from Fond du lac.

Sadly, the mansion is gone and the Terrace is not a coveted address anymore. But the Munger name is instrumental in making Duluth a bustling port city.

Samual Snively followed the lead of many pioneers who formed Duluth. Known as a plunger, he dived into any scheme or idea that met his fancy. Through that awesome instinct combined with a tolerance for risk, he served as Duluth’s mayor for 16 years. He also developed Seven Bridges Road and the Skyline Parkway.

Educated in the east, he knocked about Alaska and other areas for a while. He finally settled in Duluth, establishing a law practice, with a partner, in 1886.

Blind in one eye, large and stern, Snively didn’t drink or smoke but always had a pocketful of cigars to pass out. Though he never married, he later lived with a niece and loved following the antics of a great nephew.

Using his own money, Snively established what is now the Seven Bridges Road that winds over and around Amity Creek. Originally with nine wooden bridges that deteriorated, after he paid for and donated the scenic roadway to the city, they preserved it with seven stone bridges. He donated 60 acres of land to the project and also raised other donations of land and dollars.

While mayor, Snively oversaw the construction of Duluth’s Skyline Parkway, which was his passion.

Considered the father of the Duluth Parkway System, he loved his city.

In 1934, standing on what would become known as Hawk Ridge: “When I become discouraged, I say to myself: I should have gone to another city to seek my fortune. But when I look over these hills and see the great natural beauties of our community, I console myself and wonder where in all this wide world could I find such a view as this?”

He didn’t have his own children, but loved Fairmount Park. Using donated funds for food and transportation, he would host 500 orphans for a day each summer, take over a park for a huge picnic and let them view zoo animals.

Although he was so instrumental in developing parkways, Snively himself walked or was driven around. He had fears from several accidents he was involved in, as well as the complication of his blind eye. However, in his lifetime he attended President Abe Lincoln’s Gettsyburg Address and was also part of the Alaskan Klondike Gold Rush. From 1921 to 1937, Duluth’s Grand Old Man worked hard to make Duluth the most beautiful city of the north. Many of the amenities that make the city what it is are due to the vision of a man who willingly plunged in to get things done.

“My life here in Duluth, like that of many of my contemporaries, has had its success and its disappointments, but always lived in support of measures I believe designed for the common good of this city and its people,” Snively said.

Born to New Englanders who settled here early in American history, Chester Congdon had an English background and was deeply steeped in the Methodist Church.

Clara Hesperia Bannister, his future wife, was also the offspring of a Methodist whose father was instrumental in founding a Methodist College in California. Meeting at Syracuse University, it took 10 years before Chester felt established enough to marry Clara.

Moving to Duluth in 1892, he was armed with a Minnesota attorney's law license. Like other northeastern pioneers, he dabbled in all sorts of iron and steel investments, banking, farming and advising many businesses and trade associations.

Eventually, Chester made his fortune and they built the $22 million dollar (in today’s money) Glensheen Mansion on the shores of Lake Superior. They raised their large family there and descendants occupied the property until a daughter was murdered there in a famous 1970s murder case.

The mansion is now the property of the University of Minnesota Duluth and attracts visitors from around the world.

The Congdons donated much land that was later developed as schools and parks in the Congdon area of Duluth. They also stayed active in the Methodist Church, were instrumental in Republican politics and educated their children at fancy schools in the east.

Clara was a female college graduate when such species were rare. Although she worked at women’s schools in Canada, after she married she devoted herself to raising her seven children, her adopted nephew, and to the Methodist Church.

As for Chester, he is memorialized thus: “Those who really knew Mr. Congdon found in him a man of tender heart and warm, human sympathies. His philanthropy was general and quite well known, although he sought to keep it undercover and shrank from publicity in this regard. He was a close student of government and state policies, a foe of waste and inefficiency, a friend of political progress as he saw it, a champion of clean public life and sound government. He was always the good citizen, eager to have his part in every forward movement in directions that he judged to be wise.”

Dorothy Olson, later Dorothy Arnold, grew up in West Duluth, the daughter of a train brakeman. Her mom Clara was a Duluth native. Dad Victor, went by the name “Arnold” and Dorothy later adopted an abbreviated version of her middle name Arnoldine for her stage name. The Norwegian beauty graduated from Denfeld High School in 1935.

By age 12, she was performing on stage and singing with the Salvation Army Band. She acted in school plays and sang with an orchestra. She toured with a company out of Chicago, took dance lessons and began to get parts. While singing for NBC in New York she was offered a screen test in Hollywood.

Universal Studios offered her a film contract and she did 16 movies in two years from 1937 to 1939 — including with star Bela Lugosi. She met baseball star Joe DiMaggio on a film in 1937 and they married in 1939.

Their wedding was described as a gigantic carnival. Married in a San Francisco cathedral, Dorothy had just converted to Catholicism. It took 15 minutes to cram into the church for the wedding and one woman fainted in line. Media reports of the day say that 10,000 to 20,000 well-wishers lined the streets after the wedding to get a glimpse of DiMaggio. Italians especially turned out in droves. Lucky in life but not in love, Dorothy gave birth to a son, Joe DiMaggio III, but soon after, they divorced.

Her second marriage didn’t work out either, but she and her third husband ran a successful supper club in California where Dorothy performed. She also toured as a nightclub singer and had guest appearances on some 1950s television shows.

Dorothy Arnold’s classic beauty and great talent led her a long way from West Duluth and dancing on the Lyric stage. Her roots remained Midwestern, where she diligently visited her parents and three sisters. But her wings flew her to California to follow her sunny dreams.

Sarah Burger Stearns | Room 13

Nationally-Renowned Women’s Rights Champion & Founder of Northwood Children’s Home

Although Sarah Burger Stearns used her speaking and writing ability to fight for women’s rights, it is not anything that she saw come to complete fruition in her lifetime.

A great intellectual, thinker and activist, she was bitten by the women’s suffrage bug at age 14 when she attended an 1850s women’s rights convention with lectures by Lucretia Mott and Lucy Stone, activists, speakers, abolitionists and all around good-trouble makers of their era.

In 1858, Stearns was among 12 young women who applied for, and were subsequently denied, entry into the University of Michigan. Burger worked as a classics teacher, and after being denied admittance to the University of Michigan a second time, she was educated at a state normal school. In 1869, the University relented, admitting women, though Burger wasn’t one of them.

She wed a military man, Ozora Stearns, and, while he toured with the army, she used her persuasive powers to give public health and human rights lectures to soldiers and civic groups and she taught Freedmen.

Everywhere she lived, Sarah fired up locals for women’s rights.

She and Mary Colburn, her sister in the cause, organized women in Rochester and Champlin MN, and traveled extensively: lecturing, writing and recruiting members for the National Woman’s Suffrage Association.

Fast forward to the Stearns moving to Duluth in 1872. Sarah, with her usual gusto, dove into local causes. She and Colburn had unsuccessfully petitioned the Minnesota Legislature to allow women to vote. In Duluth, she organized women’s rights and temperance societies and served on the school board. She lobbied for women to be eligible to vote for and sit on school boards and all matters relating to schools in Minnesota. In 1875, that amendment squeaked through. Stearns educated Minnesota’s women on their new rights and helped to secure some female school board candidates in Minneapolis. She was lauded as a great leader in the local press, hosted by Susan B. Anthony when Anthony visited Duluth and served as president of statewide women’s suffrage groups.

Streams looked out for the down and out and worked on providing food and shelter for local, needy women and children. It later became Duluth’s Children’s Home, now known as Northwood Children’s Home.

Health issues caused Sarah and Ozora to relocate to California. But Sarah Burger Stearns worked tirelessly — writing, speaking, organizing, traveling — even giving a July 4th address in the 1860s — and saw the vote for women slip through her fingers multiple times in her life.

Stearns died in California in 1904 and America’s women had to wait until 1920 to get the vote.

The Neighborhood

We are located in the Old City Hall building in the heart of the Historic Arts and Theatre (HART) District. You are just steps away from restaurants, the

NorShor Theatre,

Zeitgeist Teatro Zuccone, and just a short walk down the

Lakewalk from the

Canal Park area and the famous

Aerial Lift Bridge.

Parking:

We recommend using the

Historic Arts & Theater (HART) ramp across the street for $8-10 per day or you can use metered street parking on the avenues. We do not own any of our parking facilities at this time.

Getting around:

The Historic Arts and Theatre (HART) District is a walkable area with access to many local shops, restaurants, and bars. If you want to venture further there is a public transportation stop across Superior St., local taxi companies, and Uber & Lyft available.

Frequently Asked Questions

-

Does your property have on-site front desk staff?

The Oliver Inn has no on-site front desk staff. Our staff are available to help you with your reservation or your stay from 10am to 6pm central time, 7-days-a-week. We ask guests to honor these hours and reserve after-hours calls for emergency maintenance requests.

-

How will I receive information about checking in?

Approximately a week before your arrival, you will receive the self check-in information via email. Because we are a hotel, this information tends to fall into the promotions or spam folders. If you are unable to locate it, please contact us and we are happy to send it again.

-

Does your property have on-site parking?

As a hotel in the urban downtown core, we are not able to offer on-site parking. We recommend using the Historic Arts & Theater (HART) ramp across the street for $2 per hour or $12 per day or you can use metered street parking on the avenues.

-

Can we pay when we check in?

All reservations are paid in full 7 days prior to check-in.

-

Can the complimentary drink tickets be used for cocktails?

Drink tickets can only be used for Fitger's Brewhouse craft beer. Be sure to try out our locally crafted brews from our award-winning brewery and restaurant, the historic Fitger's Brewhouse.

-

Do you have an elevator?

Yes. The Oliver Inn has an elevator. You will enter through the main door onto the 2nd Level.

-

You mention that Swedetown has Hostel-style rooms. What does that mean?

Swedetown was designed to meet the needs of price-conscious travelers. All of the four Swedetown rooms are private (unlike mosthostels which have shared bedroom models). However, they share 2 private bathrooms adjacent to the rooms.

The Oliver Inn is a perfect escape for those seeking a historic boutique experience in the heart of iconic Duluth, Minnesota.

CONTACT US

hours

Check In: 4:00 PM

Check Out: 11:00 AM

We are a virtually unstaffed hotel that is available by phone 8am-8pm daily if you need assistance.

Terms & Conditions | Privacy & Cookie Statement

Copyright © 2022 The Oliver Inn | All Rights Reserved | Powered by Cloudbeds